It’s April and the weather along the Southwestern coast of Turkey is unseasonably warm. The skies are clear, but there is a persistent haze, part pollution part particulate, that obscures and flattens the view from the hilltops.

The archaeological site of Troy has eight distinctive strata covering 3000 BC, early Bronze Age through 500 AD. The myth and magic of Troy inspired a German industrialist, Heinrich Schliemann to search for the jewels of Helen of Troy. Schliemann paid and bribed various Ottoman officials for access to the site. In 1872, he brought in equipment and dug a deep trench. This trench destroyed several priceless artifacts as it broke through at least four of the strata. It was a sacrilege.

Troy was already a tourist destination in 330 BC. Alexander the Great visited the shrine of Achilles, located near Troy, before engaging the Persian army at Issus. This city, the subject of epic poems and ancient lore, was a key port on the Mediterranean during the period of the Trojan Wars. Earthquakes and the expansion of the river deltas over the millenium, reduced the utility of the port. The symbolic and mythological importance of the site kept a bevy of Roman imperial benefactors involved in maintaining the city.

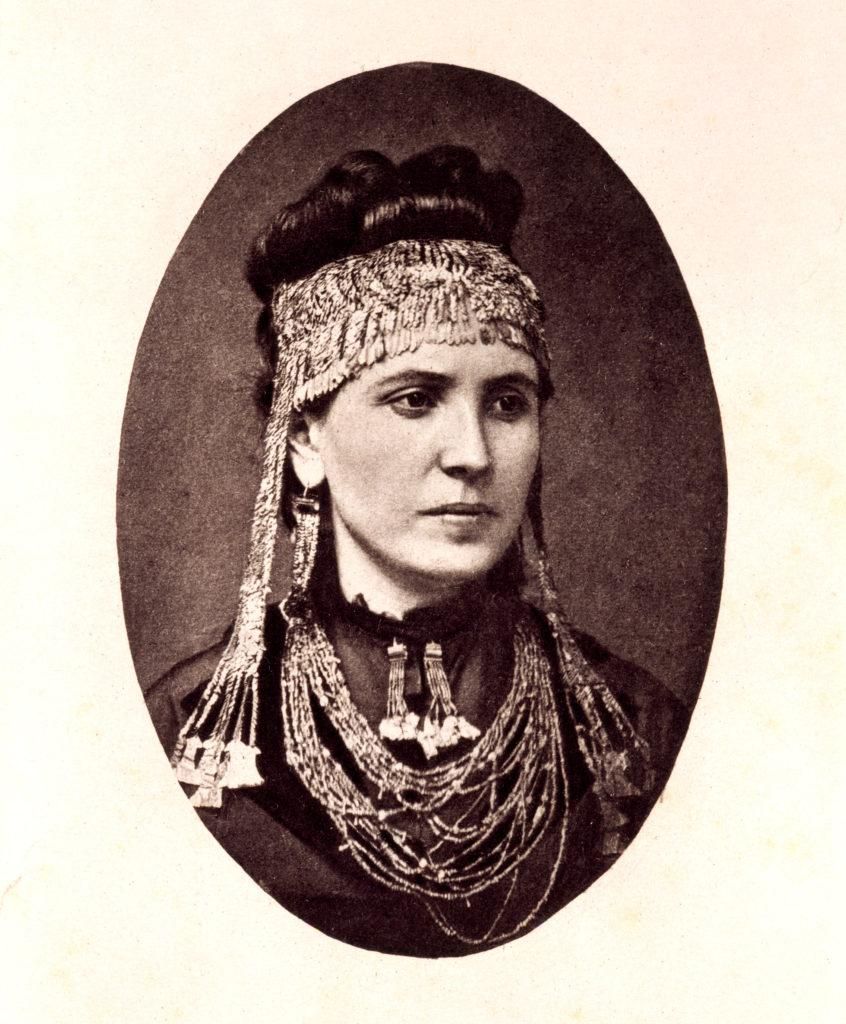

Schliemann felt vindicated in his actions as he “found” several pieces of jewelry that he stated belong to Helen. His claim was eventually debunked but he enjoyed a great deal of celebrity and notoriety for several years after the discovery.

Troy through the centuries, kept a similar footprint. Hierapolis, located near Pamukkale, expanded substantially during the Hellenistic period. The original Iron Age settlement, was established by the Phrygian’s and dedicated to the mother goddess Cybele. After Greek colonization, the temple was dedicated to Persephone and Hades. The area had been associated with both the underworld and rebirth. The Greek city was destroyed by an earthquake in 60 AD and rebuilt in a grand Roman manner. Hierapolis was also a spa destination since the 2nd century BC. The city was a healing center famous for both its thermal mineral laden waters and its doctors.

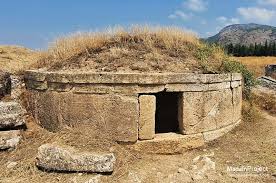

The necropolis of Hierapolis extends for over 2 km. There are over 1200 tombs, many dating to the Hellenic period, though there are also Roman and early Christian tombs. A yearly fee was paid to the city to maintain and protect the tombs. The homes of the dead could be elaborate structures that housed an entire family or two or more generations. Bodies were frequently cremated and the ashes were interred in small sarcophagi, then placed on a shelf within the structure. There are also several round graves, tumuli, that have an earthen domes.

Ephesus is only two hours away by car from Hierapolis. I’m not sure how long the 120 mile trip might take by Roman chariot or foot. The crown jewel of Ephesus is The library of Celsus, a funerary monument for Tiberius Celsus Polemaeaus, proconsul of Asia. It was unusual to have a burial within a Roman city. To get around this pesky zoning issue, Celsus paid for the library from his own personal wealth and donated his substantial personal library. His son oversaw the construction of the library, which was built to store 12,000 scrolls. The crypt of Celsus is below the library. The facade survived until an 11th century earthquake. The facade was rebuilt in the 1970’s using original fragments that were excavated at the site augmented with copies of original pieces, many of which were in either the Vienna or Istanbul archaeological museum.

Every Roman city had a coliseum, baths, gymnasium and a market place, the agora. In Perge, the Main Street, the Cardo Maximus, had a rivulet cascading through successive pools. The canal than branched east and west. This canal supplied water to two Roman baths and at least four fountains. The Cardo Maximus was positioned below the mosaic sidewalks and framed with statues. Buildings were paneled with marble. Architectural flourishes and statuary were painted. The cities would have been magnificent.

Cities of several 100,000 would not be possible without a reliable water and sewage system. The remains of a natural aqueduct system is visible In Hierapolis. Calcite deposits still coat the hillsides. This mineral also builds up and acts as a channel for the water from the hills. The early Roman engineers might have been inspired by this naturally occurring water transportation system.

Our guide, Mehmet, provided wonderfully entertaining and interesting commentary throughout our tour. His stories infused each of the sites we visited with energy and life.

Mehmet also has an excellent voice. He illustrated the acoustical quality of a coliseum by singing a mournful Azerbaijani love song from the stage of the Perge amphitheater near Antalya. The shape, slope and height of the seats, all contribute to sound cascading upwards with minimal distortion. Without artificial amplification, it’s possible to hear the words spoken from the stage at the top level of a coliseum.

Fred and I climbed to the top of the coliseum at Aspendos. This venue still hosts operatic performances and the theater was designed with the appropriate slope and dimensions to optimize sound. The angle of slope that optimizes sound was the same angle that optimized my trepidation when walking down from the top tier. The descent to the stage level was treacherous, the slick stone steps with centuries of wear and tear coupled with my own inadequate sense of balance, made for a heart pounding, fear induced trek. Going up is always easier than walking down.

I survived – which is great because we’re off to Cappadocia.